Writing a Lisp, Part 4: Environments

Last time we added pairs (and therefore also lists) to our interpreter. That’s great because we’ve built all of the data structures we need to implement a full Lisp. Let’s put them to good use!

Having data is one thing, but in most programming languages you can put that data somewhere like a variable or a register or something. Our Lisp is going to support variables. In order to do that, we’re going to need to build something called an environment.

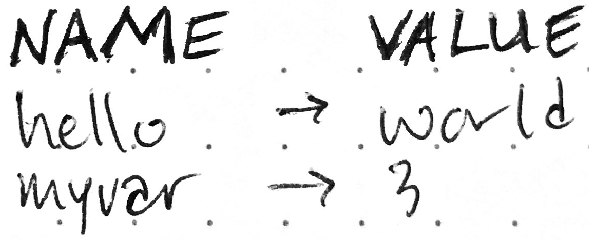

An environment is no more than a mapping of names to values:

In order to map a name to a value, use bind:

bind("numOfCars", 5, myIntEnv) (* Returns: myEnv{numOfCars->5} *)

bind("name", "Alice", myStringEnv) (* Returns: myOtherEnv{name->Alice} *)

It’s important to note that bind does not modify the environment – it

instead returns a new copy of it such that lookup will return the new value

bound.

If we were to, say, try and find the value of the variables, we could write code like so:

lookup("numOfCars", myIntEnv) (* Returns: 5 *)

lookup("name", myStringEnv) (* Returns: "Alice" *)

And that reads in English like “look up the value attached to the key ‘name’”.

The only problem with this is that our environment has to have one single type.

If we were to try and build an environment that can contain both 5 and

"Alice", we would have to wrap them in some kind of wrapper type. Good news

— we have one!

If we adapt bind and lookup to conform to OCaml’s requirements, it would

look something like this:

bind("numOfCars", (Fixnum 5), lispEnv)

(* Returns: myLispEnv{numOfCars->Fixnum(5)} *)

bind("name", (Symbol "Alice"), lispEnv)

(* Returns: myEnv{name->Symbol("Alice")} *)

lookup("numOfCars", lispEnv) (* Returns: Fixnum(5) *)

lookup("name", lispEnv) (* Returns: Symbol("Alice") *)

That way our environment can hold lobjects.

So let’s take a look at how we might represent this new type. I’d like to

represent it in terms of the types that we already have, so we can print and

manipulate them from inside the language. Makes our lives nice and easy. So how

about if we just have a list of tuples? That way the empty environment is just

Nil and our example environment would look like:

Pair(Pair(Symbol "numOfCars", Fixnum 5),

Pair(Pair(Symbol "name", Symbol "Alice"),

Nil))

In Lisp syntax, this looks like:

((numOfCars . 5) (name . Alice))

Okay, so the OCaml is kind of gross looking — I’ll admit it. But let’s write

lookup and make our lives easier.

In a Nil environment, nothing exists. So if we try and look something up, it

should raise an error. How about a new exception?

exception NotFound of string;;

The of string bit allows us to attach a value (in this case, a variable name)

to the error message. That will probably be helpful in the future.

If we’re not looking at a Nil environment, then there are two cases. Either

we found what we’re looking for in the current Pair or we need to keep

looking:

let rec lookup (n, e) =

match e with

| Nil -> raise (NotFound n)

| Pair(Pair(Symbol n', v), rst) ->

if n=n' then v else lookup (n, rst)

| _ -> raise ThisCan'tHappenError

We use ThisCan'tHappenError to ensure that we always pass in well-formed

environments. If lookup sees a poorly-formed environment (not one of the

cases we handle), we’ll know.

Alright, time for bind. If we have the above behavior in lookup, we can do

a simple O(1) append-at-front in bind:

let bind (n, v, e) = Pair(Pair(Symbol n, v), e)

bind doesn’t validate its input to make sure it’s a properly formed

environment — it just puts a new key-value pair right at the front and moves

along.

So right now we’ve got a rather flat model for environments. Most traditional Lisps and other programming languages have environments as groups of frames, which themselves group variables together. That’s really helpful when the programming language allows for variable mutation. In this Lisp, however, all variables will be immutable. This makes our jobs as language implementers easier but the jobs of the Lisp programmers harder.

For now that’s just fine! After we finish our bare-bones one-file implementation, we’ll walk through modularizing and improving the interpreter.

Download the code here if you want to mess with it.

Next up, if-expressions.