ZJIT is now available in Ruby 4.0

Originally published on Rails At Scale.

ZJIT is a new just-in-time (JIT) Ruby compiler built into the reference Ruby implementation, YARV, by the same compiler group that brought you YJIT. We (Aaron Patterson, Aiden Fox Ivey, Alan Wu, Jacob Denbeaux, Kevin Menard, Max Bernstein, Maxime Chevalier-Boisvert, Randy Stauner, Stan Lo, and Takashi Kokubun) have been working on ZJIT since the beginning of this year.

In case you missed the last post, we’re building a new compiler for Ruby because we want to both raise the performance ceiling (bigger compilation unit size and SSA IR) and encourage more outside contribution (by becoming a more traditional method compiler).

It’s been a long time since we gave an official update on ZJIT. Things are going well. We’re excited to share our progress with you. We’ve done a lot since May.

In brief

ZJIT is compiled by default—but not enabled by default—in Ruby 4.0. Enable

it by passing the --zjit flag or the RUBY_ZJIT_ENABLE environment variable

or calling RubyVM::ZJIT.enable after starting your application.

It’s faster than the interpreter, but not yet as fast as YJIT. Yet. But we have a plan, and we have some more specific numbers below. The TL;DR is we have a great new foundation and now need to pull out all the Ruby-specific stops to match YJIT.

We encourage you to experiment with ZJIT, but maybe hold off on deploying it in production for now. This is a very new compiler. You should expect crashes and wild performance degradations (or, perhaps, improvements). Please test locally, try to run CI, etc, and let us know what you run into on the Ruby issue tracker (or, if you don’t want to make a Ruby Bugs account, we would also take reports on GitHub).

State of the compiler

To underscore how much has happened since the announcement of being merged into CRuby, we present to you a series of comparisons:

Side-exits

Back in May, we could not side-exit from JIT code into the interpreter. This meant that the code we were running had to continue to have the same preconditions (expected types, no method redefinitions, etc) or the JIT would safely abort. Now, we can side-exit and use this feature liberally.

For example, we gracefully handle the phase transition from integer to string; a guard instruction fails and transfers control to the interpreter.

def add x, y x + y end add 3, 4 add 3, 4 add 3, 4 add "three", "four"

This enables running a lot more code!

More code

Back in May, we could only run a handful of small benchmarks. Now, we can run all sorts of code, including passing the full Ruby test suite, the test suite and shadow traffic of a large application at Shopify, and the test suite of GitHub.com! Also a bank, apparently.

Back in May, we did not optimize much; we only really optimized operations

on fixnums (small integers) and method sends to the main object. Now,

we optimize a lot more: all sorts of method sends, instance variable reads

and writes, attribute accessor/reader/writer use, struct reads and writes,

object allocations, certain string operations, optional parameters, and more.

For example, we can constant-fold numeric operations. Because we also have a (small, limited) inliner borrowed from YJIT, we can constant-fold the entirety of

adddown to3—and still handle redefinitions ofone,two,Integer#+, …def one 1 end def two 2 end def add one + two end

Register spilling

Back in May, we could not compile many large functions due to limitations of our backend that we borrowed from YJIT. Now, we can compile absolutely enormous functions just fine. And quickly, too. Though we have not been focusing specifically on compiler performance, we compile even large methods in under a millisecond.

C methods

Back in May, we could not even optimize calls to built-in C methods. Now, we have a feature similar to JavaScriptCore’s DOMJIT, which allows us to emit inline HIR versions of certain well-known C methods. This allows the optimizer to reason about these methods and their effects (more on this in a future post) much more… er, effectively.

For example,

Integer#succ, which is defined as adding1to an integer, is a C method. It’s used inInteger#timesto drive thewhileloop. Instead of emitting a call to it, our C method “inliner” can emit our existingFixnumAddinstruction and take advantage of the rest of the type inference and constant-folding.fn inline_integer_succ(fun: &mut hir::Function, block: hir::BlockId, recv: hir::InsnId, args: &[hir::InsnId], state: hir::InsnId) -> Option<hir::InsnId> { if !args.is_empty() { return None; } if fun.likely_a(recv, types::Fixnum, state) { let left = fun.coerce_to(block, recv, types::Fixnum, state); let right = fun.push_insn(block, hir::Insn::Const { val: hir::Const::Value(VALUE::fixnum_from_usize(1)) }); let result = fun.push_insn(block, hir::Insn::FixnumAdd { left, right, state }); return Some(result); } None }

Fewer C calls

Back in May, the machine code ZJIT generated called a lot of C functions from the CRuby runtime to implement our HIR instructions in LIR. We have pared this down significantly and now “open code” the implementations in LIR.

For example,

GuardNotFrozenused to call out torb_obj_frozen_p. Now, it requires that its input is a heap-allocated object and can instead do a load, a test, and a conditional jump.fn gen_guard_not_frozen(jit: &JITState, asm: &mut Assembler, recv: Opnd, state: &FrameState) -> Opnd { let recv = asm.load(recv); // It's a heap object, so check the frozen flag let flags = asm.load(Opnd::mem(64, recv, RUBY_OFFSET_RBASIC_FLAGS)); asm.test(flags, (RUBY_FL_FREEZE as u64).into()); // Side-exit if frozen asm.jnz(side_exit(jit, state, GuardNotFrozen)); recv }

More teammates

Back in May, we had four people working full-time on the compiler. Now, we have more internally at Shopify—and also more from the community! We have had several interested people reach out, learn about ZJIT, and successfully land complex changes. For this reason, we have opened up a chat room to discuss and improve ZJIT.

A cool graph visualization tool

You have to check out our intern Aiden’s integration of Iongraph into ZJIT. Now we have clickable, zoomable, scrollable graphs of all our functions and all our optimization passes. It’s great!

Try zooming (Ctrl-scroll), clicking the different optimization passes on the left, clicking the instruction IDs in each basic block (definitions and uses), and seeing how the IR for the below Ruby code changes over time.

class Point

attr_accessor :x, :y

def initialize x, y

@x = x

@y = y

end

end

P = Point.new(3, 4).freeze

def test = P.x + P.y

More

…and so, so many garbage collection fixes.

There’s still a lot to do, though.

To do

We’re going to optimize invokeblock (yield) and invokesuper (super)

instructions, each of which behaves similarly, but not identically, to a

normal send instruction. These are pretty common.

We’re going to optimize setinstancevariable in the case where we have to

transition the object’s shape. This will help normal @a = b situations. It

will also help @a ||= b, but I think we can even do better with the latter

using some kind of value numbering.

We only optimize monomorphic calls right now—cases where a method send only sees one class of receiver while being profiled. We’re going to optimize polymorphic sends, too. Right now we’re laying the groundwork (a new register allocator; see below) to make this much easier. It’s not as much of an immediate focus, though, because most (high 80s, low 90s percent) of sends are monomorphic.

We’re in the middle of re-writing the register allocator after reading the entire history of linear scan papers and several implementations. That will unlock performance improvements and also allow us to make the IRs easier to use.

We don’t handle phase changes particularly well yet; if your method call patterns change significantly after your code has been compiled, we will frequently side-exit into the interpreter. Instead, we would like to use these side-exits as additional profile information and re-compile the function.

Right now we have a lot of traffic to the VM frame. JIT frame pushes are

reasonably fast, but with every effectful operation, we have to flush our local

variable state and stack state to the VM frame. The instances in which code

might want to read this reified frame state are rare: frame unwinding due to

exceptions, Binding#local_variable_get, etc. In the future, we will instead

defer writing this state until it needs to be read.

We only have a limited inliner that inlines constants, self, and parameters.

In the fullness of time, we will add a general-purpose method inlining

facility. This will allow us to reduce the amount of polymorphic sends, do some

branch folding, and reduce the amount of method sends.

We only support optimizing positional parameters, required keyword parameters, and optional parameters right now but we will work on optimizing optional keyword arguments as well. Most of this work is in marshaling the complex Ruby calling convention into one coherent form that the JIT can understand.

Performance

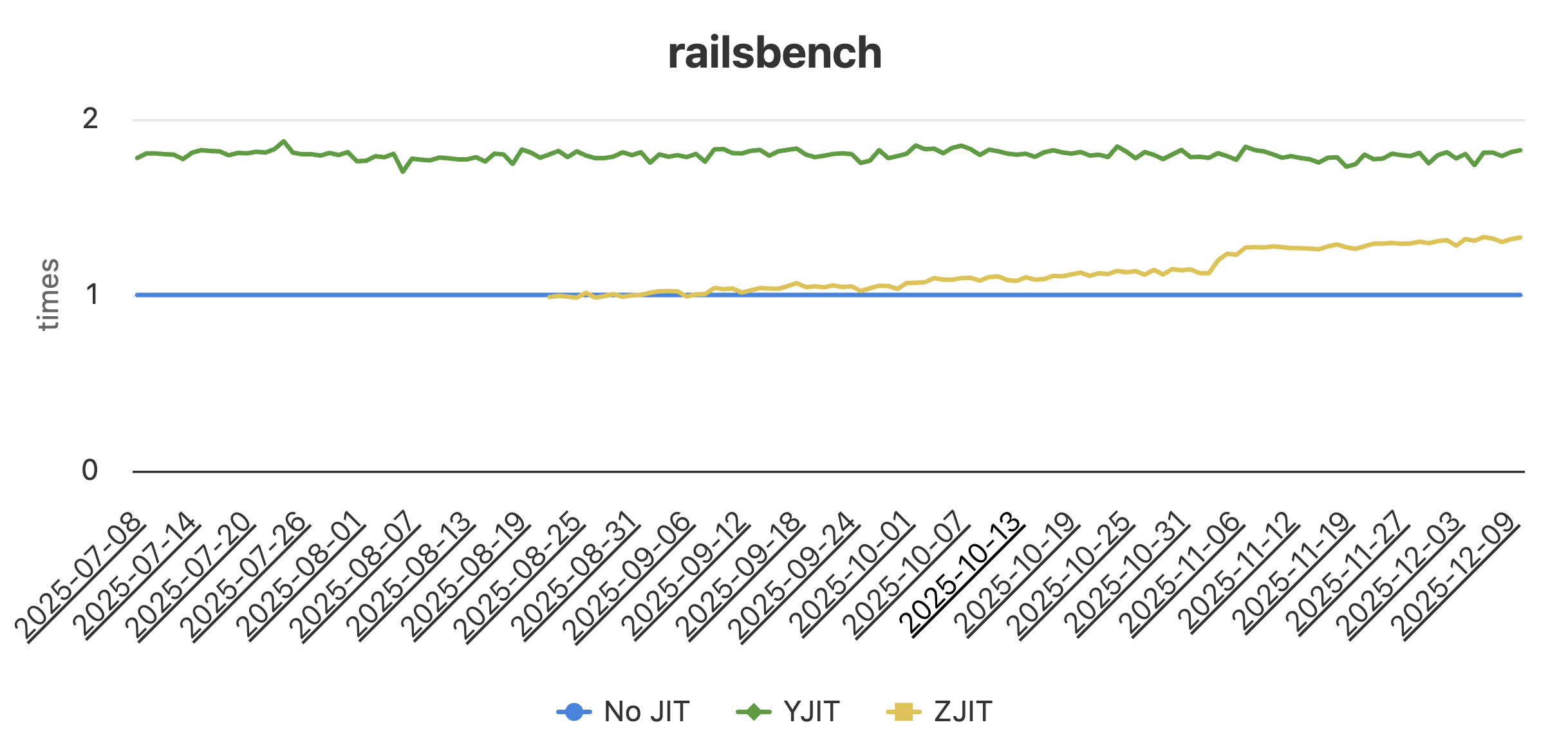

We have public performance numbers for a selection of macro- and micro-benchmarks on rubybench. Here is a screenshot of what those per-benchmark graphs look like. The Y axis is speedup multiplier vs the interpreter and the X axis is time. Higher is better:

You can see that we are improving performance on nearly all benchmarks over time. Some of this comes from from optimizing in a similar way as YJIT does today (e.g. specializing ivar reads and writes), and some of it is optimizing in a way that takes advantage of ZJIT’s high-level IR (e.g. constant folding, branch folding, more precise type inference).

We are using both raw time numbers and also our internal performance counters (e.g. number of calls to C functions from generated code) to drive optimization.

Try it out

While Ruby now ships with ZJIT compiled into the binary by default, it is not enabled by default at run-time. Due to performance and stability, YJIT is still the default compiler choice in Ruby 4.0.

If you want to run your test suite with ZJIT to see what happens, you

absolutely can. Enable it by passing the --zjit flag or the

RUBY_ZJIT_ENABLE environment variable or calling RubyVM::ZJIT.enable after

starting your application.

On YJIT

We devoted a lot of our resources this year to developing ZJIT. While we did not spend much time on YJIT (outside of a great allocation speed up), YJIT isn’t going anywhere soon.

Thank you

This compiler was made possible by contributions to your PBS station open

source project from programmers like you. Thank you!

- Aaron Patterson

- Abrar Habib

- Aiden Fox Ivey

- Alan Wu

- Alex Rocha

- André Luiz Tiago Soares

- Benoit Daloze

- Charlotte Wen

- Daniel Colson

- Donghee Na

- Eileen Uchitelle

- Étienne Barrié

- Godfrey Chan

- Goshanraj Govindaraj

- Hiroshi SHIBATA

- Hoa Nguyen

- Jacob Denbeaux

- Jean Boussier

- Jeremy Evans

- John Hawthorn

- Ken Jin

- Kevin Menard

- Max Bernstein

- Max Leopold

- Maxime Chevalier-Boisvert

- Nobuyoshi Nakada

- Peter Zhu

- Randy Stauner

- Satoshi Tagomori

- Shannon Skipper

- Stan Lo

- Takashi Kokubun

- Tavian Barnes

- Tobias Lütke

(via a lightly touched up git log --pretty="%an" zjit | sort -u)